As world leaders gather in New York for the opening of the 77th session of the United Nations General Assembly, far too many security key indicators are heading in a dangerous direction.

Related commentary:

Towards a more secure future through effective multilateralism based on facts, science and knowledge

Estimating world nuclear forces: An overview and assessment of sources

The nuclear weapon inventories of the nine-nuclear armed states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, Israel and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea)—are largely shrouded in secrecy: only three of the nine states have ever publicly declared the size of their nuclear stockpiles and in recent years there has been a notable shift towards a lower overall level of nuclear weapon-related transparency.

China’s detachment from the South Asian nuclear triangle

In contrast with coverage of the recent China–India border conflict, Chinese analysis of nuclear issues in South Asia has been decreasing. As pointed out by Indian, Chinese and US experts, neither China nor India has sought to insert nuclear dynamics into border tensions.

Russian and US policies on the INF Treaty endanger arms control

The 1987 Treaty on the Elimination of Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles (INF Treaty) is on the verge of collapse. The controversy surrounding the treaty has built up over several years and worsened in early 2017 following accusations by the United States that Russia had begun to deploy the missiles during 2016.

Tensions in the South China Sea: the nuclear dimension

In the sovereignty disputes in the South China Sea, there is an often overlooked strategic interest pursued by China: the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) quest for a credible undersea nuclear deterrent.

From ending nuclear testing to detecting tsunamis and missing aircraft: the wider applications of the Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) prohibits all nuclear explosions anywhere as an effective measure of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation but is yet to come into force. On 11 April SIPRI, in cooperation with the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI), held an event to discuss the CTBT and its wider applications.

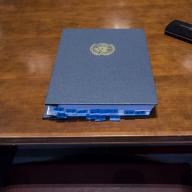

Looking beyond the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit

Some 50 heads of state and government are meeting today at the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) in The Hague, the Netherlands, to highlight their commitment to strengthening nuclear security, and to agree on measures to prevent and combat nuclear terrorism. While many states hope that the Summit will increase nuclear security, the question remains as to whether the NSS process will be successful in securing all vulnerable weapon-usable nuclear materials.

11 Nov. 2013: Time for a more comprehensive approach to the Iran nuclear negotiations

The latest round of negotiations in Geneva between Iran and the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany (the 'P5+1' states) once again failed to reach an agreement on interim steps toward resolving the long-running controversy over the future of Iran's nuclear programme. In the end, the talks faltered due to disputes over technical aspects of Iran's nuclear programme and the sequencing of sanctions relief, leaving the negotiators unable to conclude a much-anticipated deal.

Explosive potential of North Korean missiles still more diplomatic than nuclear

Today's launch by North Korea of an Unha-3 (or Taepodong-2) long-range rocket is already drawing strong negative reactions from many governments. However successful today's launch was, it does not mean that North Korea has, or is anywhere near having, the capability to launch a long-range ballistic missile strike, especially a nuclear-armed one.

Taking stock of international security

Perceptions of threats to security are both individual and shared. Currently, many share concerns about recent developments in Iran and North Korea, while many also see in the new approach of the United States a glimpse of hope. SIPRI—with its mandate to ‘contribute to an understanding of the conditions for peaceful solution of international conflicts’—aims through its annual SIPRI Yearbook to provide a basis on which threats can be assessed and to deliver the most relevant facts for the debate.

Swedish declaration on the elimination of nuclear weapons

Nuclear weapons kill immediately and kill over time. They cause devastation and environmental disaster. Twenty-five years ago a UN scientific commission warned that even a limited use of existing nuclear weapons could result in a nuclear winter over large areas over the earth. Recent findings conclude that such temporary climate change could cause the death of many millions of people. Massive use of existing nuclear arsenals would destroy all life on earth, a global suicide.

Making a new START in Russian–US nuclear arms control

Don't open the champagne just yet, but Russia and the United States are tantalizingly close to the finish line in their negotiations on a new nuclear arms reduction treaty to replace the 1991 Treaty on the Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (START Treaty). Although the fast-track negotiations in Geneva were unexpectedly diverted into the diplomatic slow lane by last-minute wrangling over US missile defence plans, the two sides are widely expected to seal the deal and sign a START follow-on treaty within a matter of weeks.