3. Peace operations and conflict management

Summary

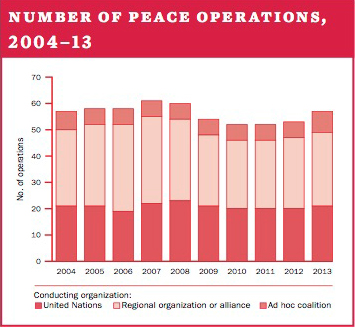

With the launch of 8 new multilateral peace operations, and with only 4 closing, the total number of operations reached 57 in 2013. France, which conducted two of the new operations, placed itself at the centre stage of peace operations in 2013, and determined much of the agenda.

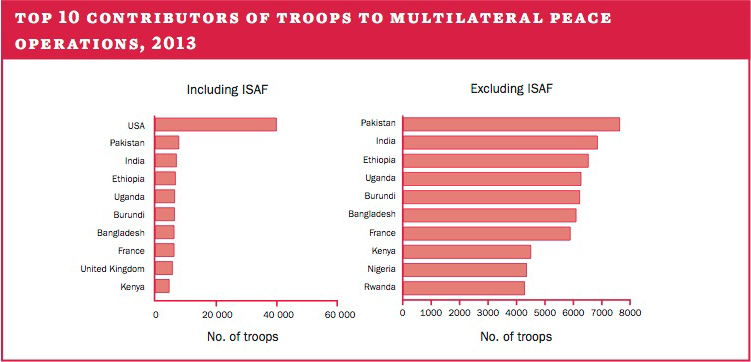

This increase was accompanied by a dramatic decrease in the total number of personnel deployed on peace operations—from 233 642 in 2012 to 201 239 in 2013— primarily due to the drawdown of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. It is likely that total personnel figures will fall further in 2015. While some personnel will remain in a new North Atlantic Treaty Organization mission in Afghanistan and other European countries may follow France to Africa, or start contributing to United Nations operations, this is unlikely to make up the ISAF-related personnel decrease.

Number of peace operations, 2004–2013

Peacekeeping in Africa

International attention appears to be moving from Afghanistan to Africa, in particular to the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mali, Somalia and South Sudan. The eight new peace operations in 2013 were all deployed in Africa, and each formed part of the complex constellations of operations, organizations and actors currently engaged there. While Africa has been the host of the greatest number of peace operations since 2010, in 2013 the drawdown of ISAF meant that it also hosted the greatest number of personnel, for the first time since 2008.

In fact, four of the eight new operations in 2013 were deployed to Mali, three to the CAR and one to Somalia. Two of the operations were African-led: the International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA), jointly led by the Economic Community of the West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union (AU), and the AU-led International Support Mission to the CAR (MISCA). With Africa increasingly taking care of its own affairs through the deployment of these missions, the question of whether Africa is ready for this task became more important.

Developments in Africa in 2013 may suggest increasingly robust peace operations, as reflected in the peace enforcement character and intrusiveness of certain missions. The new Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) of the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) was mandated to ‘prevent the expansion of all armed groups, neutralize the groups, and to disarm them’. Although it did not use such counterinsurgency language, the mandate of the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was also more robust than is usual for a UN mission. Furthermore, in an unprecedented step, the UN expanded its logistical support packages for the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) to the frontline units of the Somali National Army in their joint fight against the Islamist group al Shabab. In another controversial step, MONUSCO became the first UN operation to deploy unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or drones) for surveillance.

Top 10 contributors of troops to multilateral peace operations, 2013

Global developments

The protection of civilians remained high on the agenda of multilateral peace operations, despite difficulties in implementation. MONUSCO’s FIB showed a renewed determination to protect civilians and was generally hailed as a success. However, by the end of 2013 the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) was protecting tens of thousands of South Sudanese civilians on its bases and comparisons with safe areas in Bosnia and Herzegovina were already being made.

Consensus in the UN Security Council on controversial issues such as the use of force and the use of UAVs was found on an ad hoc basis. However, more structurally, the so-called Hollande doctrine—named after French President François Hollande—of short and limited humanitarian interventions mandated by the Security Council in cooperation with forces deployed by a regional organization, and at the invitation of the host state, appears to be similar to China’s view on interventions. In fact, Operation Serval in Mali and Operation Sangaris in the CAR determined much of the agenda in 2013.

Yet, as tensions clearly increased between the AU, the UN and African regional organizations over the transitions in Mali and the CAR, it may be questioned whether deploying missions in complex constellations is really the way forward and whether these two countries will become blueprints for future peace operations.