3. Armed conflict and instability in the Middle East and North Africa

Overview, Ian Davis, Dan Smith and Pieter D. Wezeman [PDF]

I. The Middle East and North Africa: 2016 in perspective, Dan Smith [PDF]

II. The Islamic State in 2016: a failing ‘caliphate’ but a growing transnational threat?, Ian Davis [PDF]

III. Military spending and arms transfers to the Middle East and North Africa, Pieter D. Wezeman [PDF]

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) remained at the heart of global security concerns throughout 2016. A variety of factors explain the region’s seemingly chronic insecurity and persistent susceptibility to armed conflict, such as governance failures in most Arab countries, the still-unfolding consequences of the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the US-led coalition, and the complex relations and rivalries among regional powers. In 2016 at least 7 of the 16 countries in the region used military force in combat on their own territory, and 11 used it on the territory of other countries.

A key element in MENA’s security profile is the aftermath of the 2011 ‘Arab Spring’. Five years on, it is only in Tunisia that the flowers bloom, although the country’s path to a stable democracy remains fraught with risk.

Syria

The war in Syria has resulted in the displacement of half the population—over 4.8 million as international refugees and over 6.3 million as internally displaced persons—and the death of over 400 000, although there are no reliable casualty statistics. Amid the complex array of contending forces in Syria, in 2016 the balance of power tilted quite sharply in favour of President Bashar al-Assad as a result of three important developments: the Russian air campaign in support of the Syrian Government, combined with ground force support from Iran and Hezbollah; Turkey’s reconciliation with Russia, and its ensuing policy shift from regime change in Syria to securing continued Turkish influence; and the defeat of anti-government forces in eastern Aleppo in December 2016. By the end of the year, the United States had been sidelined in the regional peace talks, and Iran, Russia and Turkey were at the forefront of discussions about Syria and Assad’s future.

Libya and Yemen

Libya ended 2016 still mired in the chaotic aftermath of the 2011 civil war and international intervention, and still seeking a pathway to stability and security for its citizens.

The interstate relationship that is the highest profile, most complex and most dangerous in the region is that between Iran and Saudi Arabia. One major issue that exacerbates poor Iranian–Saudi relations is Yemen, which has experienced an inter-mittent civil war since 2004. Saudi and other Arab forces have been involved since 2015. By the end of 2016, the Saudi intervention was associated with a major humanitarian crisis and had failed to inflict decisive setbacks on Houthi forces.

The Islamic State

The Islamic State (IS) remained a potent force and focus of international concern in 2016, despite the fact that it suffered significant setbacks in Iraq, Syria and Libya. The framework of Operation Inherent Resolve, the US-led global coalition formed in September 2014, continued to set the pace for external military operations against IS in 2016. While the core membership of IS remains in Iraq and Syria, its efforts have been reinforced by a network of foreign fighters and affiliate groups in several countries across four continents. Terrorist attacks attributed to the group or to individuals that it has inspired cost hundreds of lives in the wider Middle East, Africa, South Asia and Europe in 2016.

IS relies on infrastructure and institutions more usually associated with a state, such as oil sales, taxation, cash holdings, the sale of antiquities and ransoms, as well as access to national or international financial systems. These revenue streams are also key points of vulnerability; targeting them has been the focus of an international economic war conducted by several states that has both a military dimension (e.g. airstrikes against oil infrastructure, cash holdings and key IS financial operatives) and a non-military dimension (e.g. preventing donations, freezing assets and inhibiting trade with the group). International efforts were also made to combat IS propaganda and counter violent extremism more generally, albeit with mixed results.

Despite it losing territory in 2016, IS’s aims and terrorist capabilities are likely to persist in the coming years, possibly in a different and even more lethal form.

Military expenditure and arms transfers in the Middle East

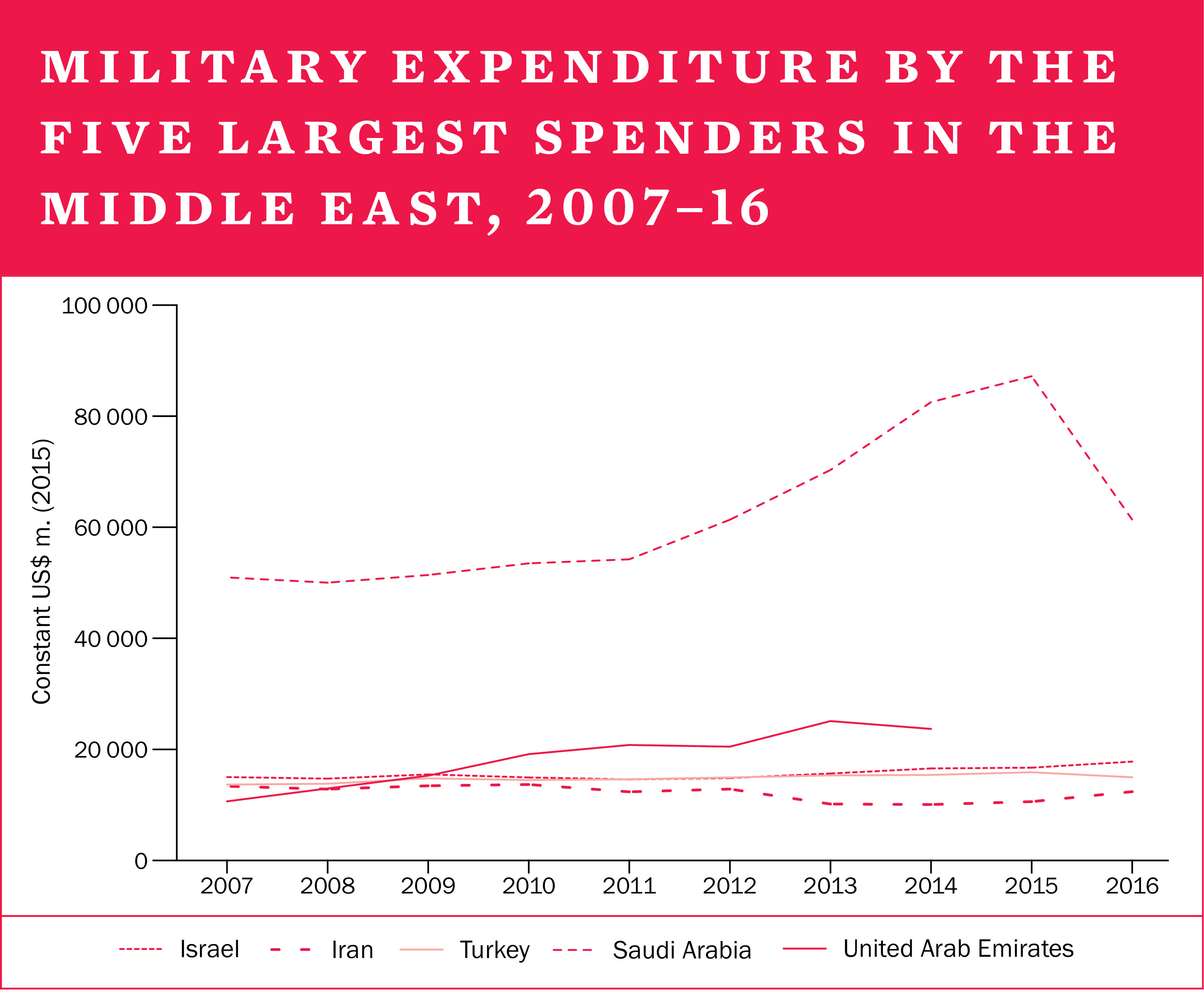

Trends and patterns of military expend-iture and arms transfers to countries in the Middle East illustrate the importance of military capability in the region. Military expenditure as a share of gross domestic product, also known as the military burden, tends to be particularly high. Total military spending in the Middle East in 2015 and 2016 cannot be calculated due to missing data. This reflects a general lack of transparency and accountability on military matters in the region. Saudi Arabia is by far the largest military spender in the Middle East, and was the fourth largest in the world in 2016.

Arms imports to the Middle East increased by 86 per cent between 2007–11 and 2012–16. The Middle East accounted for 29 per cent of global arms imports in 2012–16, making it the second largest importing region for that period. Many countries in the Middle East have acquired sophisticated military systems that seem likely to substantially increase their military capability. The USA and several West European states continued to be the major arms suppliers to most countries in the region throughout 2012–16. It is likely that arms imports have contributed to the instability, violent conflict and human rights violations in the region.